On December 14, 2022, Inki left us. We said goodbye to him at noon, allowing him to go to sleep for a final time, at peace, without pain and fear. However, I do not want to remember him only as a fragile, emaciated old man whom we carried in our arms on the last journey.

Inki lived twelve years full of fun and variety, as Earth’s most majestic creature, being full of grace, style, and inexhaustible inventiveness in finding ways to procure food (whether it was his, someone else’s or in the garbage).

2010: The Saga Begins

Let’s start with the fact that Inki was not our dog from the very beginning. He was born in South Africa on March 15, 2010, in the Palcatanda kennel. He came to Poland to join Ewa Cuper’s Virgo Vestalis kennel.

During his life with Ewa, he became a dad (with a much older partner). More importantly, he started to show his character and sheer dogged determination.

We are told that a pounding pattern has been established: Kropka pounding Inki, Inki pounding Bob, and Bobo, having no one to pound under him, planned a sophisticated revenge and cultivated cold feelings for his stepbrother that would last for years.

2012-2015: Era Getyńska

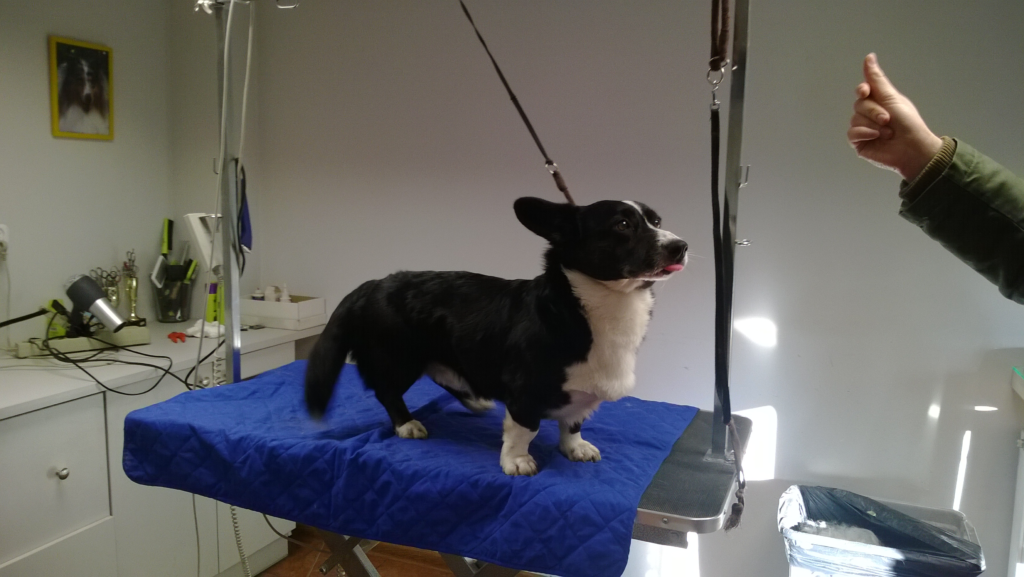

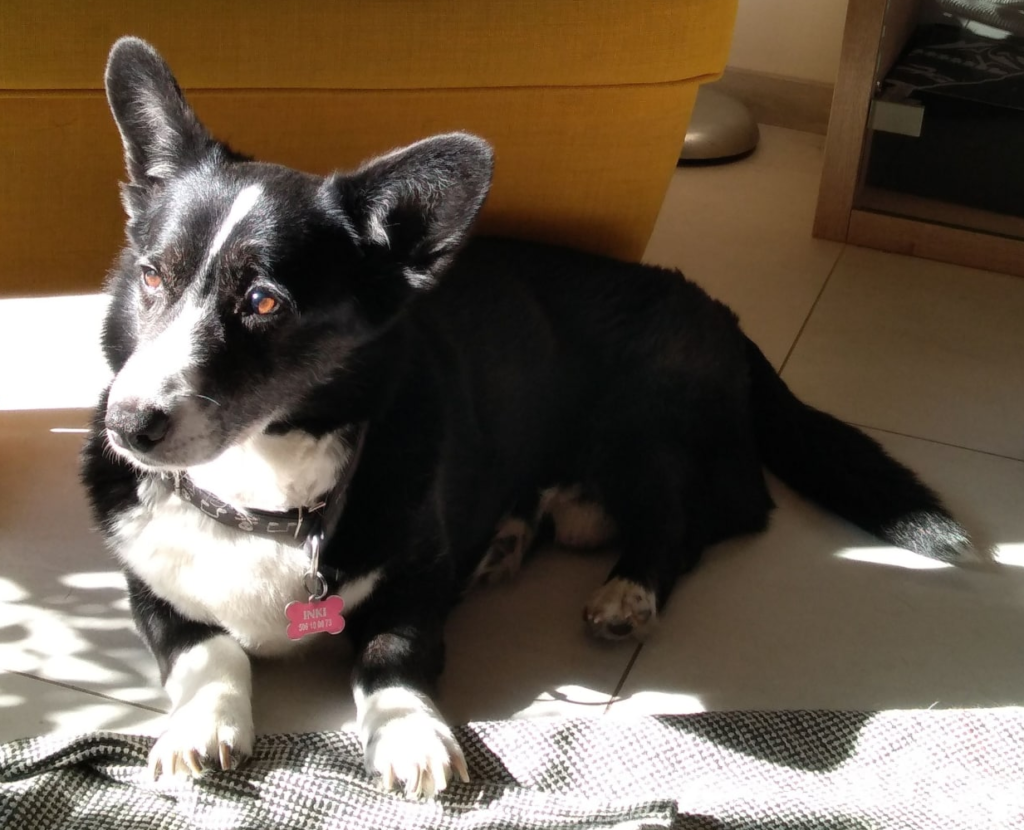

We adopted Inki in June 2012, when Ewa was forced to close the kennel and find new homes for her dogs. We decided to grab Inkspot. In terms of coat, he was formally a tricolor, but actually he had a pitch black fur splashed with dazzling white, observing the world with beautiful chestnut eyes.

In a word, it was a beautiful exterior concealing an affectionate devil.

The hrabinger of things to come was his first visit to Piwoniowa, shortly after picking him up at the train station in Poznań (when we still had a train station, rather than an insultingly small annex to a gigamall).

Maria instantly secured his eternal adoration and loyalty with a thrown ball and a belly rub, as he sprawled out on the grass, slightly out of breath. He stuck out his fluffy chest for pets, as if he was saying, “Let’s seal the pact.”

With a stroke of her hand, Maria became his Lady, a heavenly goddess, and I… I became the Boss.

Still, Inki was devil’s incarnate when it came to dogs. Apart from sealing the pact with Maria, he also:

- Immediately waged war on Scotty,

- Tried to make love to Lilli,

- Scared the living daylights out of Amos, to the point that Amos fled to the basement and refused to come out until Inki disappeared.

Relations with pembrokes remained tense for many years and abounded in various, not necessarily happy adventures. Amos was virtually the only one to avoid Inki’s teeth and courtship, apart from one incident on New Year’s Eve when our black devil decided that Amos looks mighty attractive and…

Right, moving on.

Inki left for Germany with us in July, arriving in our new flat in Rosdorf, near Göttingen. The time spent at An der Stupe 2 was one of the happiest in our lives.

We renovated the flat using our own funds and strength, in exchange for lowered rent. We painted every damn surface using white and red paint. Inki, still adapting to the new reality, accompanied us, observing his new lair. He always picked a vantage point allowing him to see what his humans are doing.

He usually did it by leaning against freshly painted doors or paneling, decorating it for years with his furs.

We also found fur in paint cans.

Or on brushes.

Or walls.

Saying that corgis shed is an euphemism.

Now, the flat itself was part of a coop. Volksheimstaette actually asked us to get consent from half the families in the building, so that we could live with Inki there (Germans are big on democracy). In practice, we just had to get two more families to sign on, since we already had a share in the coop and counted as one vote.

We didn’t have to put much effort in. We still remember Mrs Denti, fondly, as after a litany of troubles related to the previous owner’s dogs, she decided that she shouldn’t get prejudiced towards people and signed the agreement.

Inki won people over with his charming style, silence (seriously, we didn’t know a quieter dog, he barked only with Pembroks), and sociability. Once, while cleaning up after him, an elderly German thanked Maria for cleaning up, because for all its advantages, cleaning up after you dog isn’t a reflex in Germany.

At another time, a German took in interest in Inki, calling him a cute crossbreed. Inki promptly replied with an indignant growl.

Naturally, living with a cardigan forced us to adapt our daily routine and ensure he got his daily long walks. This was not difficult at all in Rosdorf, because as a backwater village in the foothills of the Harz, Rosdorf was surrounded by fields, woods, hills, and even horse farm!

Inki immediately showed us that sports are his passion – in particular, long-distance sprinting, high jumps, and fetch, of course. Retrieving whatever we threw was an element of every successful outing, especially since such exertion fatigued the dog to the point he would collapse on his muzzle back home and fall asleep. Sometimes, he was so tired that he was unable to return on his own power. He would make it clear by sitting and glaring, at which point we picked him up and carried him home – sometimes to the very door of the house.

By the way, these long walks weren’t always planned.

Once we had to walk together from Rosdorf and An der Stupe to Göttingen. The reason? I went outside with Inki, for a quick walk, fresh after waking up and having coffee. The problem is, I didn’t take my house keys with me when I left, and locked us both out. One option was to wait five or six hours for Maria to return.

The other was the Long Walk(tm).

Inki and I took a walk, covering the kilometers using an improvised leash. I wore flip-flops, and genuinely wondered if I would be taken for an inmate from one of the local psychiatric clinic. Imagine Maria’s face when our two muzzles appeared in her window at Grako.

She took mercy on us and the way back was with a bus ticket and house keys.

Just to clarify: The division of labor was due to our work! Since we started living on our own, I have been working as a freelancer from home, and Maria commuted to work at the University in Göttingen.

She always used the bus. Inki soon learned to associate her with the bus’ arrival. When he saw her on the lawn in front of the house, he’d dash from the windowsill to the door, full of joy, dancing and barking at the door.

Of course, he wasn’t a couch potato. He accompanied us pretty much everywhere.

The coolest memories include brave Inkspot walking with us for hours around Berlin, marveling at the world, sharing his opinions with German dogs at teeth-point, chasing sticks in the Tiergarten, and when he was overcome fatigue – sitting and chilling with us on a bench.

Or rather under it, as he dug himself a sort of roost in the soil.

Another trip took him to the North Sea, where he showed how a dog with his back to the wall behaves: Inki loathed water, and our attempt to break his aversion (by taking him out a few steps into the sea and trying to immerse him in ankle-deep water) ended in panic, screams, and ripping off Maria’s bikini bottom.

That changed with dog school. Inki was enrolled at the dog school in Klein Lengden, ten kilometers from home. We regularly rode bikes with him there, with Inki traveling in a luxurious trailer (he could never sit still inside and traveled peeking out of it whenever possible).

586 / 5,000

Translation results

Translation result

He taught us many things then. He showed that puppies that accost an adult, serious cardigan quickly learn to keep their distance, regardless of whether they are small and adorable or large enough to spit on his head.

More importantly, he was forced by another dog to overcome water phobia: During a particularly hot summer, the teacher decided to hold a class near a cool creek. A cheeky young Labrador took Inki’s stick – the holiest of holies! – and left it on the other side of the stream.

Inki was forced to swim over. He took a dip and realized that he’s not actually a dog, but a black, furry fish!

He fell in love with water and swimming, which greatly improved our trips to the Leine water lock, where he swam like a four-legged pike, making other dogs keep their distance. He was doing great, at least until he developed an unrequited love for the branch that was actually a part of a sunken tree.

After a failed attempt to retrieve it, he panicked slightly – but before I was able to drop my pants and swim to the rescue, he came out on the other side to the shore, snorted, cursed, then swam back over all wet and displeased.

It is worth noting that dissatisfaction did not mean insubordination or lashingout!

We quickly taught Inki to wait politely for food to be served – and to eat it only after he heard “Bon appetite!” Such savoir-vivre greatly simplified giving him food, meant less violently snatching his bowl out of our hands, and also taught him to spit out what he had in his mouth on command. This readiness to obey was a shock to our fellow corgi owners, who rarely mastered the skill. Most just started eating faster the moment they heard the command.

But the choice of food… Well, I tried the Poznan approach once and bought the infamous yellow food. Inki loved it, he ate it with enthusiasm, but at the same time, it caused terrible, terrible flatulence. Honestly, it smelled like something straight from the killing fields of the Somme or Ypres. We generally decided not to give it to him, but I had the spectacularly bad idea to give it to him one more time.

Now, Inki liked to curl up on a pillow next to Maria and keep her company like that. Coupled with the yellow food…I still remember my wife’s shriek “Michał!”, coming from the other end of the apartment, as well as the breathtaking “atmosphere” in our bedroom.

But food is not just these monstrous events. It’s also fun! How could you forget his love of apples? Inki loved to find food, and he absolutely loved apples. Cattle (one of his many nicknames) had a favorite apple tree near the house. Whenever he went out for a walk, he reared up on his legs and grabbed an apple down, for lunch.

He probably liked the mouthfeel of an apple bursting in his maw and the joy of tearing it to pieces. He also loved cardboard for the same reason, in particular rolls of toilet paper or towels. He took them to his bed then systematically tore each one to shreds. He knew that he was allowed and enjoyed this privilege very liberally. In fact, he was known to just steal cardboard rolls from the trash to play with.

One of these came with bonus content once. I was just writing an article for work (content marketing was my primary source of income at the time), when I heard Maria’s shriek. “Don’t look at Inki!” she screamed, so of course, I looked at our dog. There he was, standing in the doorway, with a cigar in his mouth, looking like Winston Churchill.

Except the cigar was a soiled tampon. Inki did not see anything wrong in the situation, and his gaze said “Come on, why the fuss?”

Did I mention that he had a talent for breaking and entering? Whenever he got the chance, he’d break into the pantry and eat to his heart’s content. During the North Sea trip we forgot to ensure he didn’t have access to food. When we came back we found a black, furry ball of contentment full of highly nutritious dog food, making happy noises as he laid back.

Inkspot, Inki, Inkowski, Czarny, Mroczny, Puci, Puć, Pan Puciński, Puciasty, Bydełko, Bydl, Czarna Cholera…

List of Inki’s nicknames

2014: *crack*

The key event in Inki’s life and ours was his discopathy. Inki was a very active and lively dog and it eventually bit him back in his black furry arse. In October 2014, we noticed a very disturbing slowdown in Inki (imagine a dog consistently running at 110% power suddenly barely getting up and walking), then a problem with moving, and eventually pain, complete with squeals and paralysis.

We were at the university clinic within the hour. It turned out that it was a herniated spinal disc. It wasn’t a total disaster, as Inki still had his motor reflexes and deep feeling. We decided to pursue pharmacological treatment and stabilization (in no small part because we were poor at the time).

I remember to this day that in the amok of that evening, I left my wallet on the bench in front of the clinic. I realized it half an hour after leaving it and several kilometers away. We promptly returned, tense as hell – but since it was Germany, the wallet was where I left it.

Inki stayed in the clinic for two weeks. During the halfway visit, we actually saw our little disoriented gremlin rolling along on a stretcher, covered by a purple towel (the towel then accompanied us for the next eight years, until it was so worn that it no longer looked anything like a towel and had to be thrown away).

At the end of those two weeks we got Inki back, stabilized, still not walking, along with his medical documentation and a bill for 1200 euros.

(We paid it in installments. We want to thank everyone who supported us, especially Adam Dudziak, who paid a quarter of the bill without expecting anything in return. Thanks, Adam! As usual, fellow dog owners proved more empathetic than regular humans, including a Belgian forumgoer, who really hated me and went on a rant to tear me down that I didn’t prepare for my beloved dog to have a spinal injury.)

Inki returned home and rehabilitation began, during which we learned a lot. The greatest lesson for me? A disabled dog incapable of controlling his bowels should not sleep in a fabric dog house. Even if it dries quickly and is easily washed off in the shower, you shouldn’t do it if you value your sanity.

Inki’s rehabilitation was improvised: His illness coincided with the end of Maria’s doctoral scholarship and a significant drop in income. We persevered, in no small part thanks to Rosdorfers: They cheered Inki on, helping him regain fitness with moral support. We practiced every day, everywhere we could, including a small square with apple trees, where Inki was an important competitor for the fallen apples.

The four-legged connoisseur loved to wander from apple to apple, helping himself to them and savoring each bite (leaving bitten apples behind whenever the taste was not to his liking). Fortunately, it was more fun than annoying for everyone. By mid-November 2014, he finally staggered to his feet, and by March 2015, Inki was walking again, without support. It was still unstable, prancing, and generally amusing to watch, but he was walking again.

The most important thing for him, however, was that he could feel his butt. More specifically, butt-pets. The blissful, angelic expression of a dog who just regained feeling in the most pleasant place on his body was priceless and made March 8, 2015, a particularly joyful day.

Inki decided to celebrate in his own way and soon preyed on half a roasted guinea fowl left on the table by us. He took it down, then consumed diligently and thoroughly, to the last bone.

To this day we do not know how a dog who freshly regained the use of his legs managed to climb onto the table and take the bird down without breaking the plates. It’s such a crazy event that Maria even got a tattoo of the event, to commemorate Inki and his display of canine magic.

2015-2019: Plewiska

In the same year, our story took another turn. It was pointless for us to wait for Maria’s PhD thesis defense for years, which wouldn’t happen for another seven (!) years, so we decided to migrate again.

The return to the bosom of the Republic of Poland took place in July 2015. After a relatively short period of searching for a home, we found ourselves in Plewiska, on Kminkowa. It’s a strange place: A townshp-sized bedroom for Poznań, a place without an urban center, developed without order or a plan, utterly chaotic – yet with plenty of opportunity for exploration and taking a dog out for a walk. A place full of nooks and crannies where you could explore.

We also felt sentimental, as it was here, among fields of wheat and sunflowers, that our love blossomed, accompanied by “Corgi on Ice” performances by the one and only Scotty, the aforementioned Fatso corgi.

Unlike Rosdorf, Inki did not gain immediate popularity. Through no fault of his own, of course. Mrs. Janina, who lived next door, was a retired nurse from Polna, and always hated our bicycles and “dirty” dog (who offended her by not wiping his paws before entering), and the father from upstairs, who hated everything and everyone.

Ironically, it was his family who saved us when, having gone outside with Inki, I locked myself out of the stairwell… With rice boiling.

It can be said that the Plewiska period is Inki’s zenith. Yes, he was disabled, but at the same time he was full of spirit and fully rehabilitated. He was not afraid of anything. In fact, many younger dogs could learn from him, the way his stubbornness and determination drove him… Which was not always a good thing.

He retained his talent for seeking out and securing food, our consent notwithstanding. He demonstrated, back in Rosdorf, that he had a very wordly taste: Tampons, apples, guinea fowl, cardboard, and even a Chinese rose, a gift I received that fell prey to him one morning.

Two years after his return, he climbed onto the table at night and devoured half a sheet of chocolate cake. Another time, a whole package of Merci (chocolate candy) fell prey to Inki’s maw.

Theobromine? What is this, some kind of dog treat?

Inki, if he could talk about the supposed toxicity of chocolate

Not to mention the meat he devoured like an egg-eating snake, all at once.

Or our tears. We are not afraid to cry, and Inki loved it – he could show his support for his Bosses, while lapping up salty delicacies and making horrifically satisfied noises!

However, social ties were the most important. For me, uprooted from Poland and moved to Germany, the return was an opportunity to once more re-enter society, to renew my friendships – including the most important one, with Piotr. Piotr is my best friend, right after my wife. He’s my brother from another mother, and a fan of Inki despite his fur allergy.

For Inki, this meant much more intense contact with people and animals. We are not talking just about regular walks, during which his majestic presence turned heads.

No, Inki was an integral part of our life, a true companion unafraid of late-night parties in the pub, endless barbecues, or overnight visits to friends.

Inki, often simply called our Doggo, was extremely sociable and polite, often stealing the spotlight and becoming the evening’s star attraction, especially in dog-friendly Piwna Stopa and later Wściekły Chmiel, our favorite pubs.

Of course, as befits a dog with an attitude, clashes happened. At Stopa, he once came face to face with an Akita Inu. The Akita started out approaching us for a cuddle and ended up trying to turn Inki into meatballs.

Fortunately, the Akita’s boss and a well-thrown chair prevented Inki from becoming a culinary staple!

This was an exception to the rule. Normally, Inki was the bully, not the bullied one.

Honestly: Inki picked either a warrior or a barbarian class at birth, living by a simple rule “Pound bitches, pund dogs”.

At Piwoniowa, my family home, he absolutely refused to follow the established order, as mentioned before, and his attitude did not improve with age. The best we could hope for was a kind of détente between Fatso and Inki (Amos preferred to remain unaligned and pretend he wasn’t there), enforced by the Interbosspeople Arbitration Committee: Vigilantly avoiding flashpoints, separating the boys when we were about to go somewhere, and constantly looking over our shoulder to pre-empt another dogfight.

This was not always successful, and incidents occurred. Inki’s ferocity combined with his experience and determination meant that we had to reac as quickly as possible. Inki did not believe in limited conflict or mere display of superiority. No, he evidently read Carl von Clausewitz’s Vom Kriege at Göttingen, and consistently applied the concept of absolute war to his relations with other dogs.

To introduce into the philosophy of war itself a principle of moderation would be an absurdity.

Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege

Our attitude played a role here. Emotional tension or nervousness about the proximity of Inki and Fasot could make clashes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

As proof, I can present the absolutely unstaged shots of these two gentlemen walking peacefully on one leash – and I assure you, they did not come to blows five minutes later (fun fact, Maria’s time at the gym made her buff enough to separate Inki and Hercules, two 15 kg dogs, by lifting both of them by the fur on their back and holding them apart in outstretched arms, prompting widespread surprise).

In time, both gentlemen gave up and the division into the Inkowski and Grubsoński Blocks disappeared, although smaller conflicts continued to smolder. Other dogs also quickly learned that Inki is a nice guy, but only as long as you followed his rules. He made an exception for girls, of course, especially in heat. He treated us once to a howling concert, simply because a female dog was in heat next door.

Returning to Poland also allowed him to reconnect with his children, although as an absent father – or rather a co-author – he typically ended his visits to children and grandchildren kicked out and retreating in fear of fangs.

On the other hand, the first meeting with his son Theodore prompted absolute surprise: Inki was strong, but relatively small, and did not resemble his son at all. They looked a bit like Flip and Flap (after we pried them apart and made them chill out).

Inki never had any problems with humans, however. He accompanied us every step of the way, moving around the house like a shadow (we can’t count how many times we nearly lost our teeth when he was in stealth mode, lying right under our feet). He was so ingrained in our lives, so present, that it became a reflex to wake up and greet him, to look under our feet, so as not to lose life or limb when grabbing our morning coffee, and whenever we had trouble at work, exchanging glances with him and together weeping over humanity and its condition.

Inki often exchanged glanceds with us while peering from his nest. Everything on the floor could be a nest, a place of calm reflection and extremely comfortable sleeping. It could be a towel, a T-shirt, an open backpack – and when we went outside, he’d usually dig in the ground, creating a hole in which to lie down and rest.

He especially liked a spot by the gazebo on Piwoniowa, where he would lie down on hot days. He only stopped digging holes then when my parents sealed it off with a stone slab. Any attempts to bury the hole and eliminate the tripping hazard were quickly undone by the canine excavator.

2017: The Alexandrian Era

In November 2017, our little Alexander appeared in the house and the Alexandrian era began.

The dog’s philosophy and approach to people paid off very quickly. We did not use any special tricks with Inki to force him to accommodate the child. Yes, he had to learn a little patience when the mini-human appeared, complete with waking up in the middle of the night and screaming. Lots of screaming.

Inki was well acquainted with loud and strange noises, after all, the Lady was a fan of heavy metal (thanks to me), and I, as a gamer, never turned down the volume (which led to funny situations, Inki once howled mournfully, while I was playing GTAIV:EfLC imitating a police siren on a car I was driving).

He was a little jealous and sneered a few times, but he quickly accepted that Alex – the mini-Boss – was a part of the family. He assumed the role of the dishonor guard, sitting by Alex and keeping an eye on him – and if he felt we were falling behind as parents, he would bring us over to make sure his mini-human was taken care of.

The obvious gain for Inki were the leftovers. Alex eventually had to learn how to eat solid foods, and through it earned the loyalty of Inki. He also loved daily walks: After Maria’s recovery and return to work, I looked after Alex, Inki, and the house. And that meant having to take my two gentlemen out every day, whether it was sleet or snow.

Inki never complained.

It helped that he had a new object of adoration: The adult Wiki became his target! Wiki never reciprocated Inki’s feelings, and the more intense he became, the more annoyance did she show. Inki frequently saw the flash of her fangs and heard the harsh bark of her annoyance, but never gave up.

Literally. Whenever he wasn’t trying to turn her into his lover, he could be a fantastic companion for her and her children. Puppies got a pass, and could count on a favorable look and a lesson in tearing sticks apart.

2019-2022: Ogrody

After Alex was born, we decided to change our residence and but a proper flat. Although nice, the apartment in Plewiska was not large enough for two adults, a dog and a child. Inki’s disability was an important factor in the search, and in the end we settled on an apartment in Ogrody. The search taught us a lot, including how pathological the housing market in Poland can be.

Most importantly, we returned to our beloved city, and Inki gained access to Rusałka, Sołacz, and mass transit, which enabled us to enjoy the whole city. Exploring green areas, unspoiled by the developers or the Poznań authorities, was pure pleasure, especially for Inki, who loved to rummage through the bushes or catch and destroy sticks of all sizes.

We remain on good terms with our neighbors, and Inki aroused sympathy in everyone. His charming nature and a wobbly, dance-like step won over hearts. He loved to exploit it, and whenever he shared the elevator with a neighbor and his shopping bag, we had to keep an eye on him.

You had to be very careful, lest Inki steal something from the bag. In his twilight years age, he left dignity behind and developed a robber’s instinct, building on his talent for securing food. It turned him into a bona fide terror of kitchens and rooms.

The beloved “victim” was Aleks, our son. Inki actually stole his mini-armchair when we moved in, deciding that it was his new nest for a while.

The dishonorable guardsman continued to perform his duties, but started to charge Alex. The dog’s toll was, of course, food, and was collected whenever possible – sometimes straight from Alex’s hands, sometimes from the table in Alex’s room… Inki demonstrated surprising agility even as his health deteriorated.

Of course, he continued to participate in outings and trips, enjoying unflagging popularity. His presence, although sometimes burdensome due to the weakening control over the excretory system (euphemism!), was crucial for maintaining sanity during the lockdown and the first two years of the pandemic.

He remained an inseparable companion, and due to the shape of the apartment (very elongated rectangle, rather than a square), he followed us all the time, keeping tabs on us. We grew uses to the sound of his claws on the tiles and panels, and the lint everywhere. Corgis shed and Inki shed intensely, to such an extent that we even found his fur in the fridge, not to mention the washing machine or the tub.

It was almost idyllic, apart from cleaning up the cheerful creativity of Inki’s intestines.

However, Inki’s edge never dulled. Sirius, my parents’ youngest corgi found out about it the hard way. During a walk through the countryside, Inki decided he wants a snack. That snack was Sirius’ malehood. The most probable flashpoint was Wiki’s ending heat. Sirius was her son, but it didn’t matter to Inki: He apparently watched Game of Thrones with us, identified him as competition, and rushed him, fangs put. Youth was no match for ferocity and experience.

We paid in blood for the incident. Literally: Sirius had Inki’s fangs around his balls, and writhed around, trying to bite back. He didn’t care what he was biting and mauled both me and my mom. In my case, it ended only with a bruised hand, while my mother had to be stitched back together, as he tore apart her wrist.

Inki felt no guilt at all.

2022

Unfortunately, Inki’s health was gaining on him.

The last year has been a slow but steady deterioration. Medication and supplements helped, together with regular veterinary interventions and injections, but over the course of a year he slowly lost control of his legs. Worse yet, his old delicacies caused him to violently explode at night (which forced me to wash the walls of our apartment and resulted in Inki spending nights in the bathtub).

To make matters worse, problems with drinking started: Inki was unable to sense that he had quenched his thirst. As a result, he could empty a literal bucket of water and ask for seconds.

And if he didn’t get a bucket? The old instinct kicked in: He looked for additional sources of water: a bucket of water to wash the floors, leftovers from the dishwasher, water from the shower, watering cans, and finally freshly watered floor plants, devoured along with the earth.

The biggest problems started in the last week of life, in early December.

Inki stopped walking, eating, and drinking. He became a shadow of himself. Although we knew that this day would come eventually and prepared accordingly… When we learned that it was either a slow death or a life of constant medication and injections for temporary relief, we fell apart. It was December 12th.

We decided to let him go. We gave ourselves other two days to say goodbye, with Inki given free reign of the house, to do anything he wanted. He could do whatever he wanted, but he chose to stay with us. Just sit with us, warm and comfortable, under a blanket. He stayed with me, Maria and Alexander.

Alex hugged him and said his goodbyes in the morning. A couple of hours later, we left for Inki’s final journey.

We took a rug, which in theory was supposed to be exclusively human and bathroom, and which Inki pretty much instantly declared to be his. We wanted to provide him with comfort in the last moments of his life, so that he would feel not cold steel, but the comfort and smell of home and the family he blessed with his presence for ten long years.

Inki was only afraid for a moment. Hugged by us, he lay on his sid, putting his head in Maria’s arms, and then fell asleep. He went away peacefully and without pain.

At a quarter past twelve on December 14, 2022, his adventurous life came to an end.

Good night, Inki. I hope we’ll meet again sometime.

“Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.”

Epitaph for Inki, Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut